Bill Scarth is a highly respected mainstream Canadian economist at McMaster University. In a piece just published by the C.D. Howe Institute, a generally conservative think-tank, he argues that the pace of federal deficit reduction should be slowed in order to lower unemployment.

His key point is that the economy still has a lot of slack which will not be quickly closed just by maintaining interest rates at their currently very low levels.

Based on quite conservative assumptions, Scarth estimates that maintaining the federal government deficit at 0.5% of GDP would lower the national unemployment rate from (what it would otherwise be) 0.4 percentage points.

The unemployment rate today is 7.1%, so Scarth's proposal would lower the rate to 6.7%, equivalent to creating some 75,000 jobs.

Scarth's argument raises an interesting question: to what extent has fiscal austerity contributed to the lack of a full recovery in the Canadian job market since the great recession?

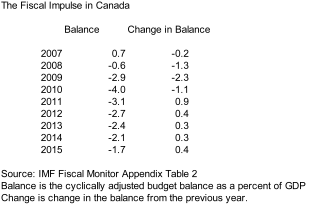

One way of getting a handle on this is by looking at the data provided by the International Monetary Fund on the “cyclically adjusted budget balance” of governments in Canada. Changes in the “cyclically adjusted” balance are not due to changes in the state of the underlying economy, but are rather due to discretionary changes in government fiscal policy, specifically decisions to change the level of spending or taxes.

For example, a fall in spending on unemployment benefits due to lower unemployment is not a discretionary cut to spending, but a deliberate cut in EI benefits would be discretionary. An increase or decrease in personal income tax revenues due to a stronger or weaker economy is not discretionary, but a cut or increase in tax rates is discretionary.

The following table shows the cyclically adjusted budget balance for all governments in Canada as a percentage of GDP, and the change from year to year. (To the best of my knowledge, nobody separates out the federal and provincial government contributions to the change in the balance.)

As shown, there was a significant change in the cyclically adjusted balance towards deficits in the years from 2008 through 2010. This was entirely appropriate, and these deficits helped reduce the impact of the great recession, and led the process of recovery in its early stages.

The federal government led the way, moving from a small surplus before the 2008 recession to a peak deficit of 3.5% of GDP in fiscal year 2009-10.

The IMF data show that discretionary policy began to work in the other direction from 2011, speeding the return to a balanced budget at a faster rate than would have happened just by leaving it to economic growth. For the most part, discretionary tightening has been led by spending cuts, especially at the federal level. The federal budget is now more or less back to balance.

Going by Scarth's numbers, discretionary fiscal tightening of 0.3 to 0.4% of GDP by the federal and provincial governments over the past four years has kept the unemployment rate higher than it would otherwise have been by about 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points.

Some would, of course, argue that governments had to turn to policies of austerity following the period of higher deficits and mounting debt during and after the great recession. Canadian government net debt rose from a low of 22.4% of GDP in 2008 to 39.9% in 2015.

But the IMF figures also show that net government debt in Canada today is less than one half the G20 average of 83.0%. And the costs of servicing the debt are very low due to very low interest rates.

Bill Scarth's advice to slow down the pace of federal government deficit reduction merits serious discussion.

Needless to say, however, it was immediately rejected by finance minister Joe Oliver.

Photo: goodncrazy. Used under a Creative Commons BY licence.