It is becoming increasingly clear that race has an impact on food insecurity. In Canada, more than 4 million people struggle with the burden of food insecurity, with a disproportionate number of Black, Indigenous and racialized Canadians identifying as food insecure as a result of enduring racialized income inequality.

As a member of the Toronto Food Policy Council (TFPC) and Board Chair of Food Secure Canada, I have contributed and participated in the creation and implementation of food policies locally and nationally. Through this work, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that the solutions from both government and the food justice community aren’t addressing the deep-seated food access and availability challenges that Black people in Canada face.

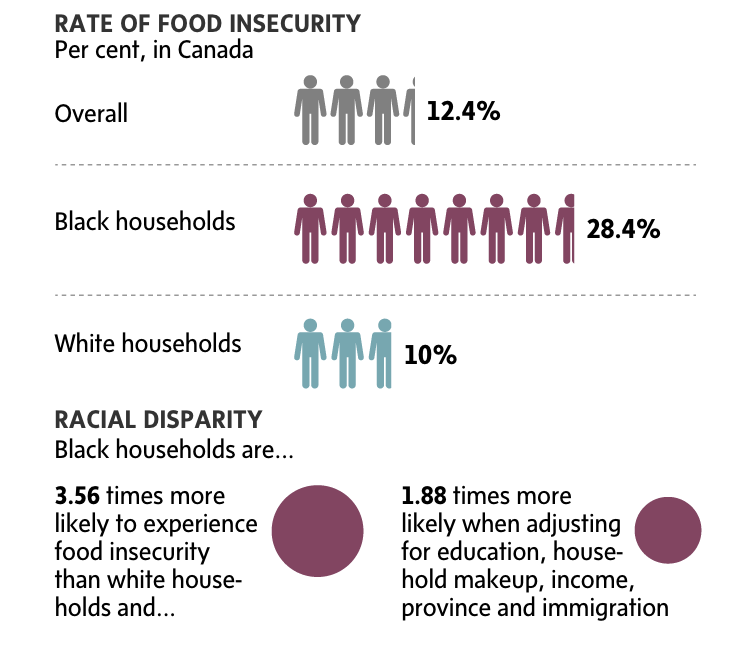

Food insecurity is defined as inadequate access to food due to a lack of income. For many Black Canadians, the overriding factor determining their status as food insecure is the simple fact they are racialized as Black. By virtue of being Black in Canada: individuals and families face a reality that is disportionately compounded by racism and poverty — shaping their particular experience with food insecurity. A recent study conducted by PROOF and FoodShare found the best predictor of food insecurity among Black Canadians was their race. Black communities are 3.5 times more likely to experience food insecurity compared to white Canadians, even after adjusting for factors like immigration status, education level, and homeownership. Black children were also 34 percent more likely to be food insecure compared to 10 percent of white children. This disparity has been linked to the increased likelihood of developing chronic diseases, like diabetes, asthma, and depression, and to poor educational and health outcomes, like learning challenges, low graduation rates and low self-esteem.

Another contributing factor is income. In Toronto, the Black community makes up the largest group of the working poor, and has the greatest representation in low income neighbourhoods. In these low income neighbourhoods, food deserts are more likely to exist, making the possibility of purchasing affordable and healthy foods even more difficult. What is most striking is the factors that usually limit the incidence of food insecurity for other racial groups — employment, household composition, education level, immigration status and home ownership — do not protect Black communities from the experience of marginal, moderate or even severe food insecurity.

Current approaches to addressing food insecurity include: food banks, community kitchens, and food buying clubs — all of which are positioned as solutions to alleviate immediate food insecurity needs, but they fail to address the scale or root causes of the problem. These approaches act as band-aid solutions which further depoliticize the issue, forcing us to question why a country like Canada is producing these sorts of inequities in the first place.

Addressing food insecurity in the Black community is about more than addressing hunger, it’s about combating anti-Black racism and intergenerational poverty through a multi-pronged intergovernmental approach, grounded in the right to food. The right to food provides a structural framework to tackle barriers to food access by acknowledging the government’s responsibility to respond to the issue with a systems approach. Doing so removes the current dependence on charity fueled models like food banks.

We need a comprehensive strategy to adequately address this issue. The best place to implement such a strategy is at the municipal level where local food assets and resources are best understood. The City of Toronto has a significant opportunity to show leadership on this issue, as home to the largest Black population in Canada. Municipalities are closest to communities, providing a unique role to deliver neighbourhood food programs, service provision, and targeted community planning and consultation opportunities to address challenges like food deserts, and the policing/securitization of grocery stores in low-income neighbourhoods. Furthermore, local governments should provide adequate funding to community-led groups and organizations who already do this work, like Afri-can Food Basket, Black Creek Community Farm and FoodShare. These organizations have a proven track record of addressing food insecurity in low-income areas where they have pre-existing relationships with Black communities — providing affordable fresh food markets and youth food programs to meet the nutrition and health needs of members of the community.

Additionally, providing income supports and meaningful economic opportunities are an important part of a comprehensive strategy. Many Black Canadians are currently under and unemployed, so among all strategies mentioned within this approach, one of the most impactful efforts would be the realization of a national guaranteed annual income and increased social assistance rates. Other income supports like the Canada Child Benefit have shown significant impact in dropping food insecurity rates by one third. A second effort would be to increase Black economic resilience. This is the focus of Toronto Community Benefits Network’s Creating Career Opportunities for Black Youth strategy, which seeks to tackle intergenerational poverty in gentrifying neighbourhoods by facilitating access and training for quality jobs.

A comprehensive approach that looks at income, decent work and access to economic opportunities will have broader socio-economic outcomes for Black populations, and has been linked to living longer, lowering the risk of diet-related disease, improved mental health, community safety and educational outcomes for Black students.

In order to bring about a real solution that tackles the root cause of food insecurity, we first need to realize that our current approach is merely a stop-gap to address a much larger systemic issue. Our real problem is the deep systemic racism that fuels racialized income inequality in Canada, sentencing Black communities to experience the debilitating struggle of food insecurity for generations to come.

Melana Roberts is a municipal and federal food policy advisor, public speaker and community advocate based in Toronto.